Introduction.

Most human cultures never have thought about writing music. Music is, in general, an issue of oral tradition. Songs are transmitted form mouth to ear, and nobody asks themselves why it should be fixed on a sheet of paper. Besides in many musical traditions improvisation is such an important element that it would be pointless writing down something that never is going to be performed in the same way.

Nevertheless, musical notations systems have been developed in many places of the world, and in some periods of history. Western Europe, India or China are some of these places.

Here you can see an example of a Chinese notation system called Quin.

And this is an example of an Indian notation system called Bhat

Musical notations in Western Europe

Several notation systems have been developed in Europe. We are going to focus in one of them that has been spread all around the world and it’s the most used today. But we are also going to give some historical perspective to get a broader picture of the different ideas that have been developed throughout history to solve the problem of writing music.

In the picture below you can see two different musical notations that are very popular today in the context of Western Music:

- This is the best known musical notation that has its origins in Europe. Today it’s used all around the world and can be apply to many kinds of music. It’s the first one (and on many occasions the only one) that comes up to our minds, when we think about musical notation:

- And this is a guitar tablature. It’s a musical notation that is linked to the practice of this instrument and that it’s much easier to read for guitar players:

Frist musical notations in Europe were originated in Ancient Greece. Greeks wrote some melodies mainly for academic purposes, to understand better their musical system and be able to describe it better. They were also interested in preserving some songs or in celebrate something by associating some written music with it. But in general, they were not interested on musical notation. Almost all their music was transmitted orally, open to transformation and improvisation. It’s because of these reasons that so little of Ancient Greek music has been preserved.

This is one of the few examples of Greek music that has been preserved till now. It’s the oldest complete musical work known to us. It’s an Epitaph, written on a funerary stone to commemorate the death of a woman:

It was in the religious context of the European Middle Ages, when people started to have a real interest in developing a way to write music, to be able to perform it always the same way.

In this period Cristian rituals (mainly the mass) were performed with music like the Gregorian Chant. Singing the songs always in the same way was of paramount importance. Because of that they developed some musical notation systems that eventually evolved in our current system of musical notation.

We are going to see how the different qualities of the sound can be written and some of the solutions people have came up with throughout time in the Western Music context.

1 Writing pitchWestern Music, since antiquity, is focus on the melodic dimension of music. So writing pitch is one of the first problems that has been to be addressed.

Ancient Greece

Los primeros europeos en abordar este asunto fueron los griegos. Desarrollaron un complejo sistema de teoría musical en el que hablaron de las notas y las escalas como base de su sistema melódico.

Greeks were the first Europeans that developed a notation system. They thought about their music and came up with a musical theory in which they spoke about notes and scales as the basis of their melodic system.

To name the notes they used the names that they gave to the strings of the lyre, and to write them they used the letters of their alphabet.

This are the notes the way they wrote them. They represent two octaves from A low to a sharper one following a descending order.

The Middle Ages

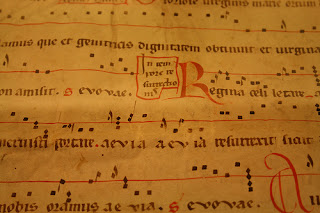

As we have already said it was in the religious context of the Middle Ages when an extensive musical repertoire was written down for the first time. In this case the repertoire was the music that was used for the Cristian rituals.

Plaint Chant rhythm (Gregorian Chant is a kind of Plain Chant) is free, so developing a precise notation for rhythm makes no sense. Rhythm will depend completely on the expression of the lyrics that are taken from the Biblie and are written in prose. So, they were interested fundamentally in writing melodies.

They invented to different notation systems to do it. The diastematic systems in which the pitch of the note is written accurately, and the adiastematic systems that represent the pitch in relation with that of the surrounding notes but without total precision.

- Diastematic notations:

There were several diastematic notations. This one is called “Dasian”. Notes are written in the left column of the score and lyrics are written putting each syllable al its corresponding level:

As you can see it’s not very practical to write long lyrics with wide tessiture.

- Adiastematic notations

In this case we are going to show you the St. Gall notation. Notes are grouped in some symbols called neumas that signal the direction of the melody. Tose symbols are located above the lyrics.

Adiastematic notations despite been less accurate were still enough for them, because at the beginning of the Middle Ages, learning music still depended on oral tradition. Musical notation helped them to remember the song and allowed them to wite down other more subtle aspects of the interpretation.

After a while, people started figuring out system that could combine the caracter of the adisatematic notations with the information about pitch of the diastematic ones. This was achieved with lines. At the beginning they started using one of two lines marking the position of the most important notes. Mainly the “finalis note” and the dominant of the songs. The pitch of the rest of them should be estimated in relation with these two lines. You can see score of these kind in the following examples.:

Aquitan notation:

Hispano-Visigoth notation. The red line indicates also in this case the finalis note of the mode.

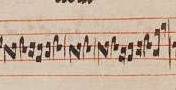

Finally, Around the XII century appeared the squared notation. This is a system basically identical to the one we use today regarding the representation of pitch.

Para ello se coloca delante una "clave" que indique cual es la nota que corresponde con cada una de las líneas. En este caso la clave sería do en tercera, que indica que la tercera línea es un do. El siguiente espacio (hacia arriba) sería por tanto re y la siguiente línea mi. Hacia abajo los espacios y las líneas correspondientes serían si, la sol y así sucesivamente en orden decendente:

It uses 4 lines, called tetragram. Notes are situated on the lines and on the spaces between them. To read it there is a symbol written in the left side of the lines that indicates the name of the notes on each line. This symbol is called clef. In this case the clef indicates that the third line corresponds with the note C. In consequence the next space over the C line corresponds with the note D and the next line would be E. Going down the tetragram gaps and lines would be B, A, G and so on following a descending order.

Modern Notation System.

Modern musical notation, regarding pitch, is identical to that of the square notation but using 5 lines instead of 4. These lines are called staff.

Clefs are also used to name the lines. The most usual are G on the second line and F on the fourth one. They are used for higher and lower tessituras respectively. Because of that they are usually called treble clef and bass clef.

This are the names of the notes written in the treble clef.

2 Writting durations

Representation of sound duration is essential to write rhythms.

Rhythm in Ancient Greek music was in tight relation with poetical rhythm. Greek poetry had two duration values: a short one that was represented as a U and a long one that was represented with this symbol _.

In Greek poetry metric was made with some basic units called “feet”. They were called like that because they used to follow the rhythm of a song with their feet. Those feet combined in many ways long and short notes values. Feet where the basic unit of either musical or poetical rhythm.

Here I’ll show you some examples of Greek feet taken from Wikipedia:

During the Middle Ages rhythm representation started to be developed with the apparition of complex polyphonic music in the 12th Century. Polyphonic music school of Notre Dame, Paris, invented a system to write rhythm based on the rhythm of Greek poetry.

To do so, it used aggrupation of certain sequences of notes. As an example, three joint notes, followed by groups of two meant to be a troqueo mode (_U):

A single note followed by groups of three a dactilicus

Groups of three single notes represent a molossus.

In the Renaissance musical notation took a form that was very similar to the current one.

Representing duration in modern notation:

- Speed

The first element that has to do with duration is the general speed of the music. To indicate it we define the duration of a reference value called crochet. This will define the beat.

In this case the general speed (or beat) is 120 crochets per minute (two per second).

This indication appears in the top left or the score and can be measured with a device called metronome.

Before the invention and generalization of metronomes the beat was indicated with some Italian words that give a general idea of the speed. Here you have a list of them:

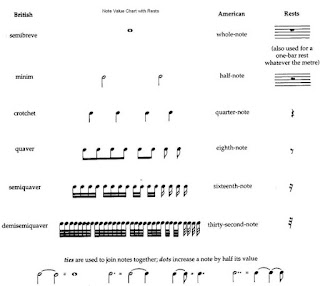

- Musical figures

Musical figures are representations of different values of sound duration.

The crochet is the figure that represents a beat. The rest of the values are represented by figures that are related between them in proportions of double or half.

That way we have the following figures:

3 Writting intensity

In music intensity is represented from two different perspectives: From the point of view of rhythm we can represent some strong beats in contraposition with weaker ones. This is called accentuation or stress. From the point of view of musical expression we also can represent the general volume in a composition.

Desde el punto de vista de la expresión se puede escribir el volumen general al que debe interpretarse una composición.

- Acentuation

This symbol > is used to represent stress on an individual beat.

Time signatures represent the rhymical organization of accentuation. So we can define time signatures as systems to organize sequencies in the accentuation of beats in a regular way to create rhythmic feelings.

That way you can stress one of two beats, or one of three beats. And you can also make subdivisions in the system.

To better understand that you can go to the part of the blog in which I deal with rhythm. Here you also can see other systems of regular accentuation of beats outside the idea of time signatures as the rhythmic modes.

In the picture below you can see the different time signatures with their accentuations:

- Intensity and expression

Intensity linked to expression is called dynamics. Music sounds louder when expressing strong energies and softer when looking to express other feelings. This is represented by Italian words and some dynamic symbols. You can see it in the picture bellow.

A partir de entonces escriben a la izquierda del primer sistema de la partitura el instrumento que debe interpretar cada parte. Puedes verlo en este ejemplo de una partitura de una composición para orquesta:

4 Writting timbre

Some medieval notations used letters above the notes that most probably were related with the emission of different vocal timbres, but it’s impossible to know how they actually did it.

Leaving this besides, composers were not really interested in representing timbres of specific instruments on the scores until the baroque period and they didn’t systematically do it till classicism.

Since then, they write the name of the instruments on the left of the first system of the staff. You can see it in this example of an orchestral score: